Data augmentation is a critical, cost-effective strategy for enhancing the performance and robustness of machine learning (ML) models. It is the process of artificially generating new, varied data from existing datasets to train new ML models.

This technique is a pragmatic response to a fundamental challenge in ML: the need for large, diverse datasets, which are often difficult and costly to acquire due to limitations like data silos, regulatory constraints, and the sheer time required for collection and labeling. By serving as a form of regularization, data augmentation enables models to better generalize to unseen data, preventing the common problem of overfitting, where a model memorizes a narrow dataset but fails to perform accurately in real-world scenarios.

What Is Data Augmentation? A Core Concept

At its core, data augmentation is the practice of artificially expanding a training dataset by applying a series of transformations to the original data.

The primary goal is to create new, modified copies of existing data points without altering their original labels. This process is vital for training deep learning models, which rely on large volumes of diverse data to develop accurate predictions. In the absence of sufficient real-world data, data augmentation provides a scalable and efficient method to increase dataset size and diversity.

This technique is used to enrich datasets by creating many variations of existing data, thereby enabling a model to encounter a wider range of features during training. The augmented data helps a model better generalize to novel inputs and improve its overall performance in real-world environments.

Why Data Augmentation Matters

The use of data augmentation is not merely a convenience; it is a strategic necessity that addresses several core challenges in machine learning model development.

First, it leads to enhanced model performance. By exposing a model to a larger, more comprehensive dataset with greater diversity, augmentation helps the model learn more robust and adaptable features. This is a critical factor in developing models that are reliable and accurate in production environments.

Second, data augmentation is a primary method for mitigating overfitting. Overfitting is an undesirable behavior where a model learns to predict training data with high accuracy but struggles with new data. This occurs when a model trains on a narrow dataset and memorizes its specific characteristics. Augmentation provides a broader dataset, making training examples appear unique to deep neural networks and compelling them to learn generalized patterns instead of memorizing specific features. The more examples available to a model, the more accurately it can define the underlying distribution of a class, thus refining its decision boundaries and improving its ability to generalize.

Third, the technique offers a solution for reduced data dependency and cost. The process of collecting and preparing large, high-quality datasets is often prohibitively costly and time-consuming. Data augmentation increases the effectiveness of smaller datasets, reducing the reliance on extensive data collection efforts. This makes it a cost-effective way to boost model performance, particularly when data scarcity is a significant bottleneck.

Finally, data augmentation can be used to address class imbalance. In datasets where one class is significantly underrepresented, augmentation can be used to generate more examples of the minority class, creating a more uniform distribution and improving model performance. This is particularly useful in fields like medical imaging for rare diseases or finance for fraud detection, where the data for certain critical classes is naturally scarce.

The fundamental problem of machine learning model development stems from the high cost and time associated with data acquisition and the inherent risk of model overfitting when data is limited. Data augmentation serves as a pragmatic and effective solution to this core development bottleneck. The challenge begins with data scarcity or a lack of diversity. This directly leads to the risk of a model overfitting and memorizing a narrow dataset. Overfitting, in turn, results in poor generalization and unreliable predictions in the real world. Since collecting more real data is often impractical, data augmentation provides a cost-effective, artificial means to introduce diversity and volume, thereby improving model performance and robustness.

Augmentation vs. Synthetic Data Generation: A Critical Distinction

Data augmentation and synthetic data generation are both techniques used to enhance datasets, but they differ fundamentally in their approach and use cases. Understanding this distinction is crucial for selecting the right strategy for a given problem.

The Core Principles of Data Augmentation

Data augmentation operates by applying transformations to existing data samples to create variations. This process fundamentally preserves the original data's core information while expanding its diversity. In essence, it is a low-risk, controlled modification of real-world data. For example, in image processing, a photograph may be flipped, rotated, or have its brightness adjusted, but the underlying content—the object or scene in the photo—remains the same. This approach is inherently tied to the statistical distribution of the original dataset, which makes it a safe choice for improving model robustness and generalization.

The Role of Synthetic Data Generation

In contrast, synthetic data generation creates entirely new data points from scratch. This is achieved using algorithms, simulations, or advanced generative models such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). The key difference is that synthetic data does not rely on existing samples for its creation; it mimics the patterns and statistical properties of real data to build a new dataset from nothing. For instance, a GAN can be trained on a dataset of medical images and then used to generate new, previously unseen medical images that exhibit the same characteristics as the real ones.

When to Use One Over the Other

The choice between data augmentation and synthetic data generation is not merely a technical one but a practical one related to risk, complexity, and the problem context.

Data augmentation is generally preferred when a good-quality base dataset already exists and the primary goal is to improve model robustness and prevent overfitting. It is a low-risk choice because the augmented data retains the statistical properties of the original dataset. Implementation is often simpler and faster, with readily available libraries automating common workflows.

Synthetic data generation is a strategic tool for more complex scenarios. It is particularly useful when real data is scarce, sensitive (e.g., healthcare records), or prohibitively expensive to collect. For example, generating synthetic patient records can advance medical research while maintaining privacy. However, this approach carries a higher risk. The quality of the synthetic data is highly dependent on the generative model's ability to accurately capture real-world patterns, and flawed generation can introduce unrealistic artifacts or subtle biases that may compromise model performance.

A comprehensive strategy may involve combining both techniques. A developer might use synthetic data generation to build a large initial dataset to overcome data scarcity, and then apply data augmentation to that dataset to further refine and increase the model's robustness.

| Key Differentiator | Data Augmentation | Synthetic Data Generation |

|---|---|---|

| Source of Data | Existing, real data | New data points built from scratch |

| Method | Controlled transformations and modifications | Algorithms, simulations, or generative models |

| Primary Goal | Expand diversity and prevent overfitting | Overcome data scarcity and privacy constraints |

| Risk Profile | Lower risk; tied to original data distribution | Higher risk; dependent on the quality of the generator |

| Typical Use Cases | Improving model generalization, handling class imbalance in existing datasets | Creating datasets when real data is sensitive or unavailable, simulating complex scenarios |

Techniques by Data Type: A Comprehensive Breakdown

The choice of data augmentation techniques is highly dependent on the type of data being processed. A one-size-fits-all approach is ineffective, as methods must be tailored to the specific characteristics of the data and the problem domain.

Computer Vision: Augmenting Visual Data

Data augmentation is a central technique in computer vision for tasks such as image classification and object detection. Techniques are often categorized into geometric and photometric transformations.

Geometric Transformations alter the spatial layout of an image. Common methods include:

- Flipping: Creating a mirror image, typically horizontally, as a vertical flip may not represent a realistic scenario for many natural images. However, a vertical flip of a medical image, such as a mass, may still be a valid augmentation

- Rotation: Rotating an image by a specified angle

- Scaling and Cropping: Resizing or cropping parts of an image. This can help models become invariant to object scale and location

- Shearing: Tilting the image along one axis.

Color Space and Photometric Adjustments alter pixel intensity to improve a model's robustness to variations in lighting and camera settings. This includes techniques like:

- Brightness, Contrast, and Saturation Adjustments: Modifying an image's RGB channels

- Noise Injection: Adding random values to an image, such as Gaussian noise, to simulate sensor noise or degradation

- Kernel Filtering: Applying filters to change an image's sharpness or blurring

Advanced Techniques have evolved to create more complex and realistic augmented data. These include:

- Random Erasing/Cutout: Deleting a random portion of an image to force the model to learn features from other parts of the object, simulating partial occlusion.

- Mixup: Blending two images and their corresponding labels via a weighted average to create a new, composite image.

- CutMix: A combination of Cutout and Mixup, where a patch from one image is cut out and pasted onto a second image, with the label being a weighted sum based on the pixel areas from each image.

Natural Language Processing (NLP): Techniques for Text

Text data presents unique challenges for augmentation due to its discrete nature. However, several effective methods have been developed to generate an artificial corpus.

Rule-Based Approaches, often referred to as Easy Data Augmentation (EDA), are simple but powerful operations, particularly for smaller datasets. These include:

- Synonym Replacement: Replacing words with their synonyms, often using a linguistic database like WordNet. This technique introduces variability without compromising the overall meaning or context.

- Random Insertion: Inserting a random word from the dataset at a random position in a sentence.

- Random Swap: Swapping the positions of two randomly selected words in a sentence.

- Random Deletion: Randomly deleting a word from a sentence.

Neural and Advanced Methods leverage neural networks to generate new text samples. A notable example is back-translation, which involves translating a text to a target language and then back into the original language. This process often introduces grammatical and stylistic variations, creating a new, semantically similar training example.

Audio Processing: Techniques for Sound

Data augmentation for audio involves modifying existing audio samples to help ML models generalize better. Common techniques include:

- Noise Injection: Adding background sounds or random noise to an audio signal to simulate real-world conditions.

- Time-based Adjustments: Altering the speed of an audio signal without changing the pitch (time stretching) or shifting the audio to the left or right.

- Pitch Shifting: Modifying the frequency content of an audio signal without affecting its duration.

Augmentation can also be applied to a spectrogram, which is a visual representation of an audio signal's frequencies over time. Techniques like SpecAugment, which masks parts of a spectrogram, can force a model to focus on broader patterns rather than fixed features, improving robustness.

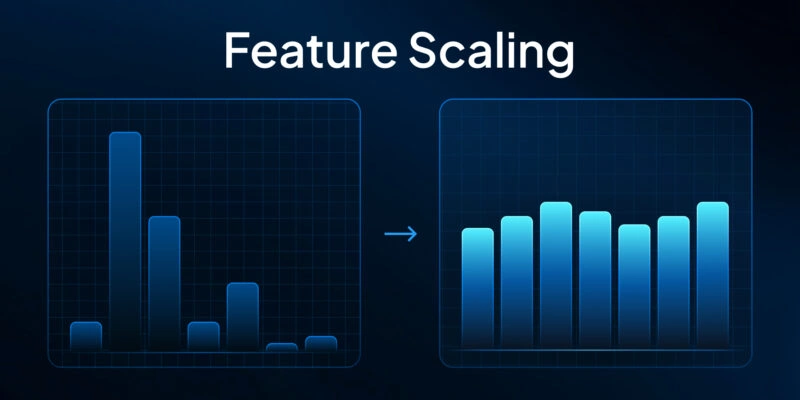

Tabular Data: A Different Approach

Traditional augmentation methods like rotation or flipping do not directly apply to structured, tabular datasets. However, alternative strategies exist, primarily aimed at improving model generalization and addressing class imbalance.

- Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE): This is a widely used algorithm to address class imbalance. SMOTE creates new instances of the minority class by interpolating between existing minority-class samples.

- Feature Manipulation: This involves perturbing numerical features with small random noise or swapping categorical values within logical constraints. This method requires careful consideration and deep domain knowledge to avoid creating unrealistic data points, such as an impossible combination of height and weight.

Real-World Applications Across Industries

Data augmentation is not an abstract theoretical concept; it is a vital technology with practical applications across a wide range of industries. These applications demonstrate how augmentation solves specific, high-impact business problems.

- Healthcare and Medical Imaging: Augmentation is a useful technology in medical imaging because it helps improve diagnostic models that detect, recognize, and diagnose diseases. It is particularly vital for rare diseases, where a lack of source data variations can hinder model training. The use of synthetic patient data advances medical research while respecting data privacy.

- Automotive and Autonomous Systems: Data augmentation makes self-driving cars safer by training them on images of roads in various conditions, such as different lighting, weather, and angles. This helps models recognize objects like pedestrians and traffic signs in all conditions, making them more robust to the unpredictability of the real world.

- E-commerce and Retail: Models in retail environments are used to identify products based on visual factors. Data augmentation can produce synthetic variations of product images, creating training sets with more variance in lighting conditions, backgrounds, and product angles. This improves the accuracy of product searches and recommendation systems.

- Manufacturing and Quality Control: The manufacturing industry uses ML models to identify visual defects in products. By supplementing real-world data with augmented images, models can improve their image recognition capabilities and more accurately locate potential defects, which reduces the likelihood of shipping a damaged or defective product.

- Finance and Fraud Detection: Augmentation helps produce synthetic instances of rare events like fraud. This enables models to train more accurately to detect these critical, yet infrequent, occurrences in real-world scenarios. Similarly, larger pools of training data enhance the potential for deep learning models to assess risk and predict future trends with greater accuracy.

Implementation, Best Practices, and Limitations

While image augmentation is a powerful tool, its effective implementation requires a strategic approach and an understanding of its limitations.

When Should You Use Image Augmentation?

The consensus among experts is that data augmentation should almost always be used to improve and regularize a model. Specifically, it is recommended to apply it:

- To prevent models from overfitting.

- When the initial training set is too small or imbalanced.

- To improve model accuracy by enabling better generalization.

- To reduce the operational cost and time of data collection and labeling.

The only instance where one might consider skipping augmentation is if the dataset is so incredibly large and diverse that augmentation provides no meaningful added diversity. For most practitioners, such datasets are a rarity.

Practical Considerations and Limitations

Successful implementation of image augmentation is not just about applying transformations; it's about doing so intelligently.

Apply to Training Data Only

A critical best practice is to augment only the training dataset and not the validation or test sets. This ensures that the evaluation metrics remain unbiased, accurately reflecting how the model performs on unseen, real-world data.

Maintain Label Consistency

Transformations must not alter the underlying semantic meaning or label of the data. For example, in a classification task, flipping a "6" might result in a "9," which would be a mislabeled augmented example and could degrade model performance. A careful, human-led review of the augmented data is an important step to ensure quality.

Finding a Balance

Excessive or unrealistic augmentations can introduce noise and actually hurt model performance. A balance must be struck where transformations simulate plausible real-world variations without distorting the data beyond recognition.

The Problem of Bias

A crucial limitation is that data augmentation does not fix inherent biases in the original dataset. If the initial data is unrepresentative of the real world, augmenting it will simply create more of the same biased data, potentially amplifying the problem. The effectiveness of augmentation relies on the assumption that the original data is a representative sample of the desired distribution. If the original data under-represents a certain demographic, augmenting it will not fix this; it will simply create more under-represented data, perpetuating the bias. This underscores the need for initial data quality analysis before any augmentation is performed.

Conclusion

Data augmentation has become a cornerstone of modern machine learning because it solves a simple but costly problem: real-world data is limited, expensive, and often imbalanced. By generating controlled variations of existing samples, augmentation strengthens model robustness, improves generalization, and reduces overfitting — without the burden of additional data collection. Across vision, text, audio, and tabular domains, the right augmentation strategy allows models to encounter more diverse scenarios and learn patterns that hold up in production.

It also serves as a practical middle ground in the broader synthetic-data landscape: less risky than fully generated data, yet powerful enough to meaningfully expand training distributions. When applied thoughtfully — aligned with data semantics, task requirements, and fairness considerations — augmentation becomes a low-cost, high-impact lever for model quality. As ML systems scale into increasingly complex real-world environments, augmentation remains one of the most effective tools for building reliable, resilient models.