Introduction to iBeta 3 and the New Standards

Imagine a biometric security fortress where iBeta 3 stands as the new gatekeeper at the drawbridge. In the realm of face recognition and biometrics, iBeta 3 represents the latest and most rigorous Presentation Attack Detection (PAD) level – a high bar set to ensure that only live, genuine users get through.

iBeta 3 is critical in today’s ecosystem because fraudsters are leveling up their game with deepfakes, 3D masks, and sophisticated hacks. Biometric verification providers asked for stronger evaluations, and iBeta answered by raising the drawbridge – introducing Level 3 PAD testing in mid-2025 to address escalating spoofing threats.

Fundamentals of Liveness Detection and Anti-Spoofing

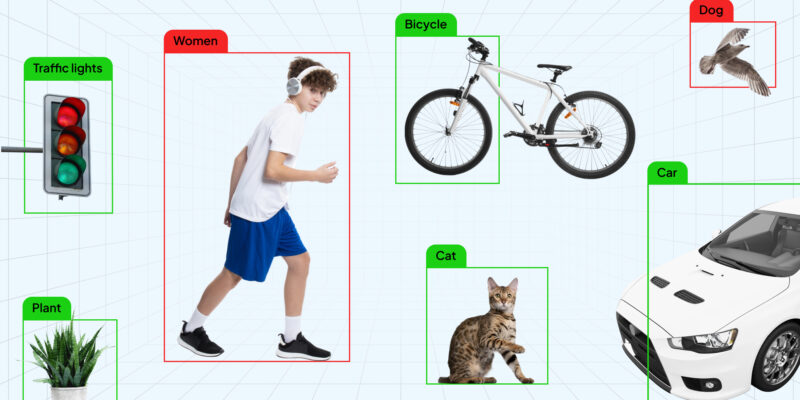

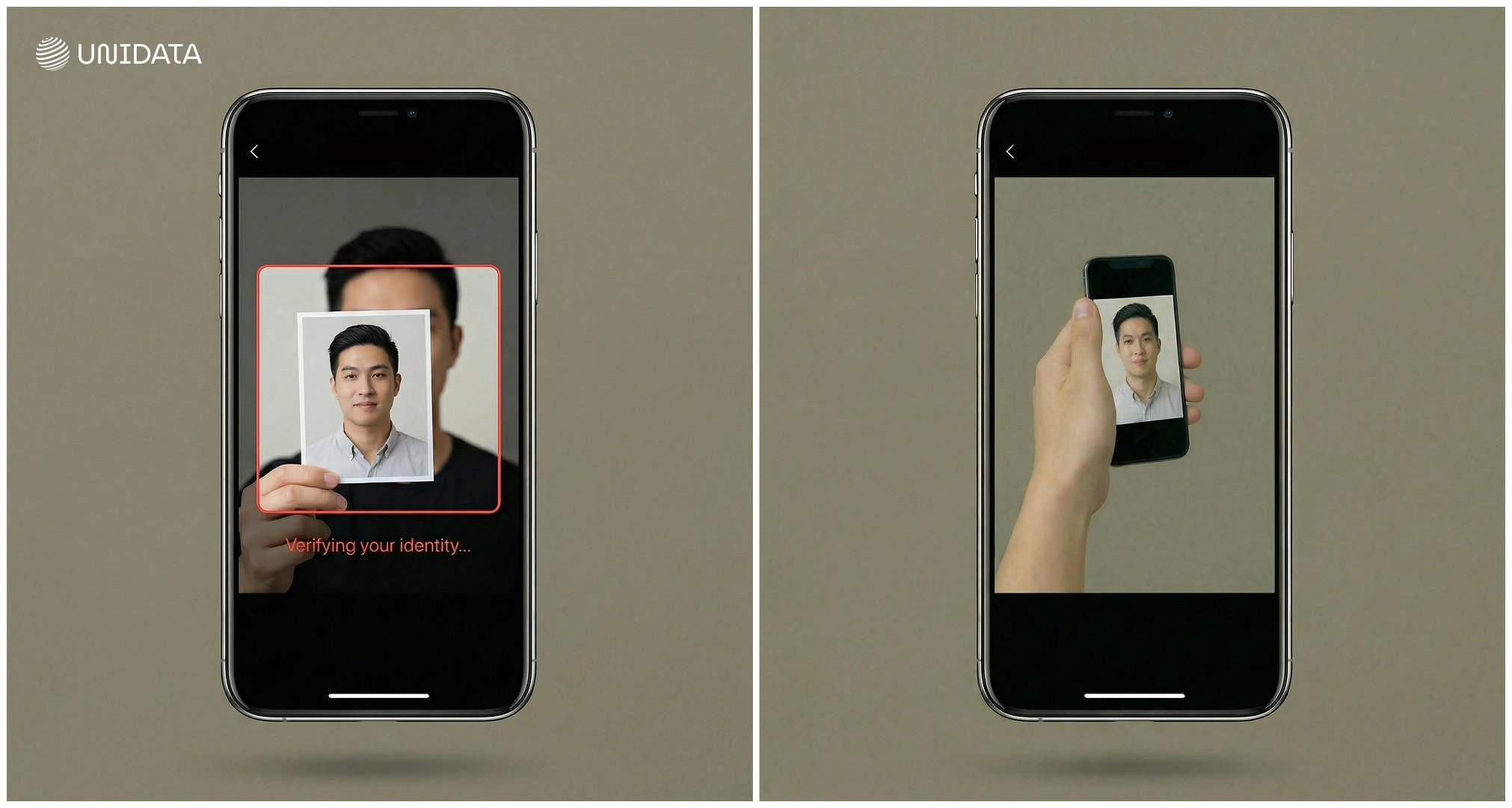

Liveness detection is what separates real users from fake ones in biometric systems. It verifies that the input — face, fingerprint, or voice — comes from a live person, not a static photo, mask, or deepfake. Without it, spoofing becomes dangerously easy.

There are two main approaches:

- Passive liveness runs silent checks for depth, motion, or skin texture.

- Active liveness prompts the user to blink, move, or speak.

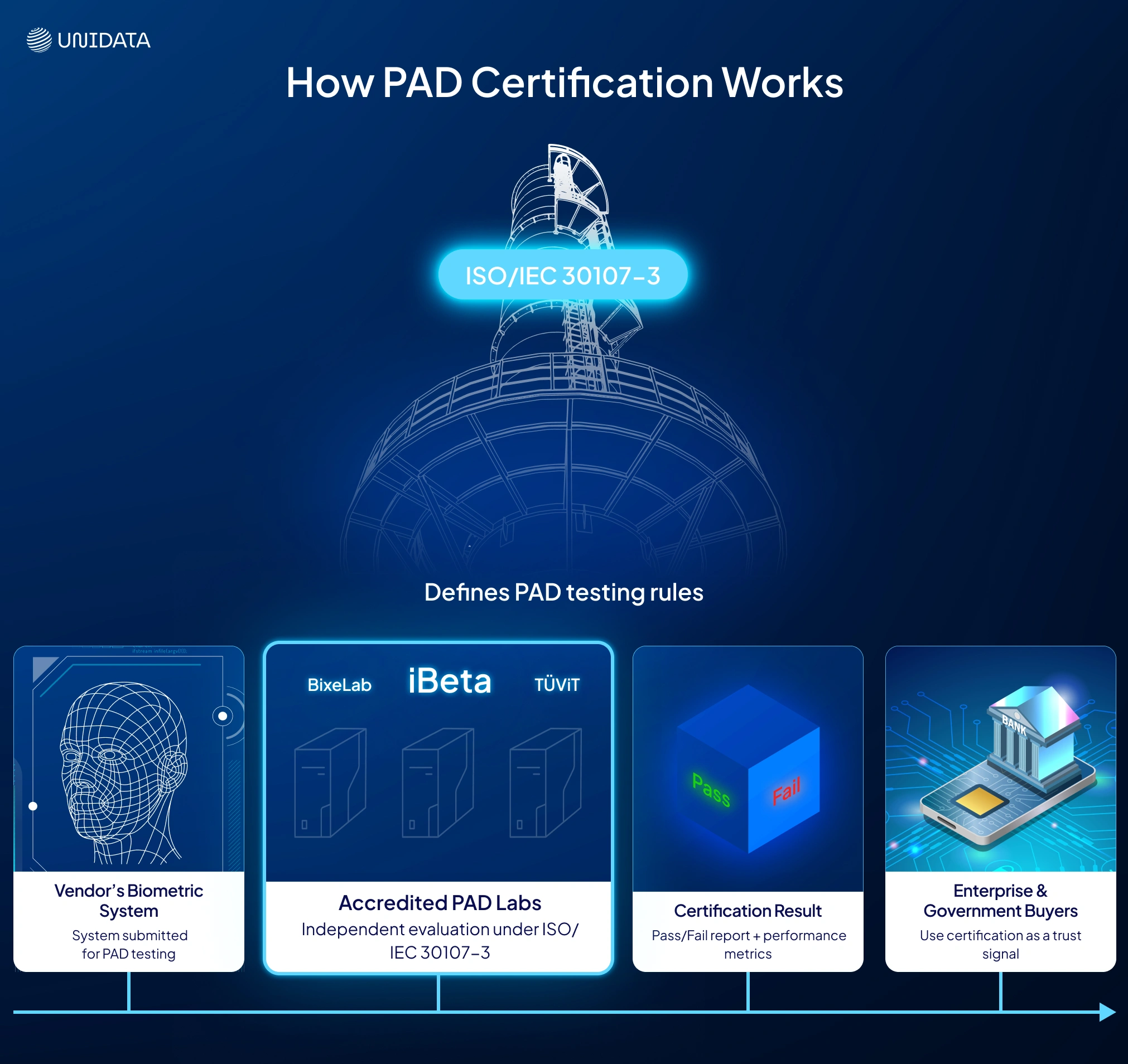

Both aim to block what ISO standards call Presentation Attacks. The global benchmark for this is ISO/IEC 30107-3 — it defines how to test a system’s ability to detect spoofs and sets thresholds for error rates like APCER and BPCER.

Multiple accredited labs apply this framework under strict conditions. While iBeta remains the most widely referenced PAD lab — especially for vendors targeting the U.S. market — it’s not alone. Other ISO-accredited testing labs include BixeLab (Australia), TÜViT (Germany), and several European institutes working with national agencies. All of them follow the same ISO rules but may differ in how they structure test plans or evaluate borderline cases.

Background and Purpose of iBeta Certification

While multiple labs offer PAD testing under ISO 30107-3, iBeta has emerged as the most widely recognized one. Based in the U.S. and accredited by NIST, iBeta has tested biometric systems against the ISO/IEC 30107-3 standard since 2018.

Their mission? To see if vendors’ “anti-spoof” claims hold up under pressure. They launch real-world spoof attacks — masks, photos, deepfakes — and issue a pass/fail report that confirms if the system meets ISO standards.

For buyers, this independent vetting is critical. It helps cut through vendor hype and validate performance. In fact, iBeta even publishes a public list of certified systems with exact software versions. That level of transparency builds trust — and makes it easier to compare vendors during procurement.

Goals and Testing Levels in PAD

Presentation attacks and PAD methodologies apply across biometric modalities: face, fingerprint, iris, voice, and more. While most real-world evaluations today still revolve around face recognition, the iBeta methodology itself is modality-agnostic. Each test is tailored to a specific system and the type of liveness detection it uses. For instance, active-liveness systems are challenged with dynamic spoofs — modified masks or animated deepfakes that react to prompts — whereas passive systems face more subtle attacks such as direct video injection into the camera feed or static 3D masks requiring no user interaction.

At the component level, iBeta calculates standard APCER/BPCER metrics; for full end-to-end systems, it uses IAPMR (Impostor Attack Presentation Match Rate), which reflects the probability that an impostor attempt will travel through the entire pipeline “from start to finish” and still be accepted as legitimate.

The standardized iBeta PAD program includes three escalating levels of difficulty, each tightening both attack complexity and accuracy requirements. In brief:

Level 1

Level 1 simulates low-effort attacks — printed photos, smartphone screen selfies, simple paper masks. Testers may spend no more than ~8 hours in preparation and no more than $30 per attack attempt. To pass, a system must block 100% of these basic attacks: APCER = 0% and BPCER ≤ 15%. The test typically includes ~900 attempts (around six attack types × ~150 trials each).

Level 2

Level 2 introduces more advanced spoofing materials and techniques, such as 3D masks, high-resolution video replays, or deepfake clips. Testers are allowed 2–4 days of preparation (about 24 hours of hands-on work) and up to $300 per attack type. A compliant system must keep APCER ≤ 1% while maintaining BPCER ≤ 15% — meaning virtually all attacks must be caught. Total test volume is around 1,100 attempts (multiple PAIs × ~150 attacks each, plus ~200–250 bona fide samples).

Level 3

Level 3 models professional-grade, resource-intensive attacks. There are no fixed cost limits; preparation time can extend up to seven days per attack type. Testers design fully custom spoofs with the most advanced tools available — hyper-realistic silicone masks, animated deepfakes, controlled digital insertions — anything capable of mimicking a live human.

To pass, a system must deflect at least 95% of attacks, as iBeta allows up to 5% attacker success to reflect the difficulty of these trials. The convenience threshold is stricter as well: BPCER must stay ≤ 10%. In other words, one in twenty highly sophisticated attacks may succeed — but no more. Level 3 test suites commonly exceed 1,500 attempts, with the exact plan tailored to the system and adjusted during evaluation.

For now, Level 3 is available exclusively for face recognition technologies — the dominant modality in remote identity verification. Other biometrics (fingerprints, iris, voice) may receive their own Level 3 programs as their threat landscapes mature biometricupdate.com.

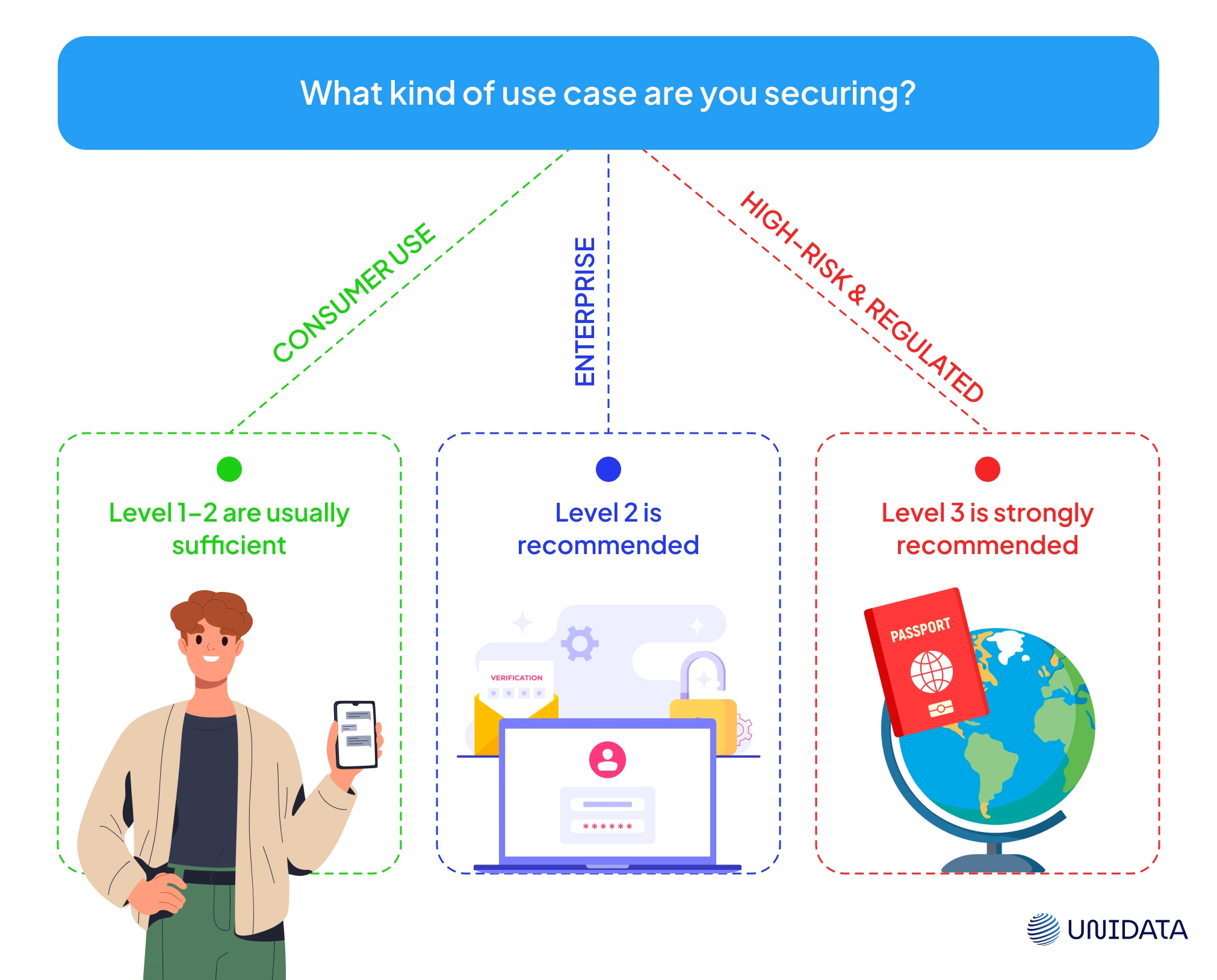

Where It Matters

Level 1 or 2 testing may suffice for consumer use — like phone unlocks or basic account access. But Level 3 is designed for high-assurance use cases: national ID enrollment, border control, and remote onboarding in finance or healthcare. These are the domains where attackers are most motivated — and where PAD failures carry the greatest risk.

In-Depth Overview of iBeta 3

Level 3 isn’t just another test — it’s a full-scale simulation of how a determined attacker would target your biometric system under optimal conditions. At this level, test teams are composed of highly experienced specialists, each with a record of at least 10 prior PAD evaluations, as required by iBeta’s program specifications ibeta.com.

Sophisticated Spoof Design

Unlike Level 1 (limited to 8 hours) or Level 2 (up to 2–4 days), Level 3 permits up to 7 days of preparation per attack species, allowing testers to engineer high-fidelity spoofs with exceptional precision. There is no fixed budget cap — iBeta coordinates directly with vendors to determine appropriate tools and materials. This enables the use of advanced 3D silicone masks, deepfake animations, and props built by professional artists.

While some earlier drafts may have described the attacker’s arsenal as “unlimited,” it’s more accurate to say that Level 3 removes preset constraints — testers have access to extensive resources, but within a collaboratively defined scope. iBeta removed the $30 (L1) and $300 (L2) cost caps in favor of realistic scenario budgets tailored to each system ibeta.com.

New Attack Types Introduced in Level 3

Level 3 raises the bar by introducing attack types that replicate real-world, high-effort fraud attempts, grounded in iBeta’s enhanced methodology and aligned with ISO/IEC 30107-3 standards.

According to iBeta’s official documentation and corroborating reports from BiometricUpdate.com, these attacks include:

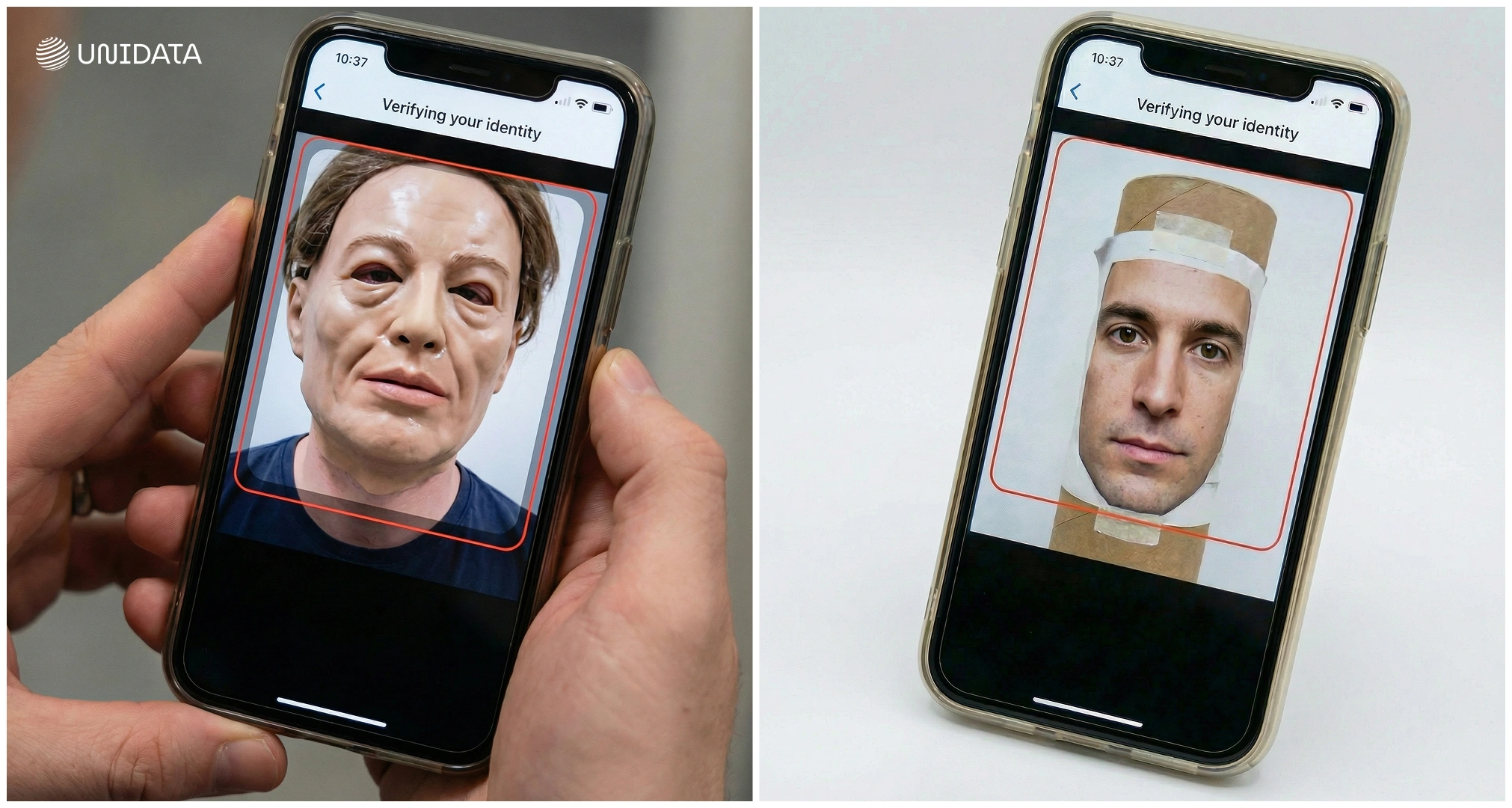

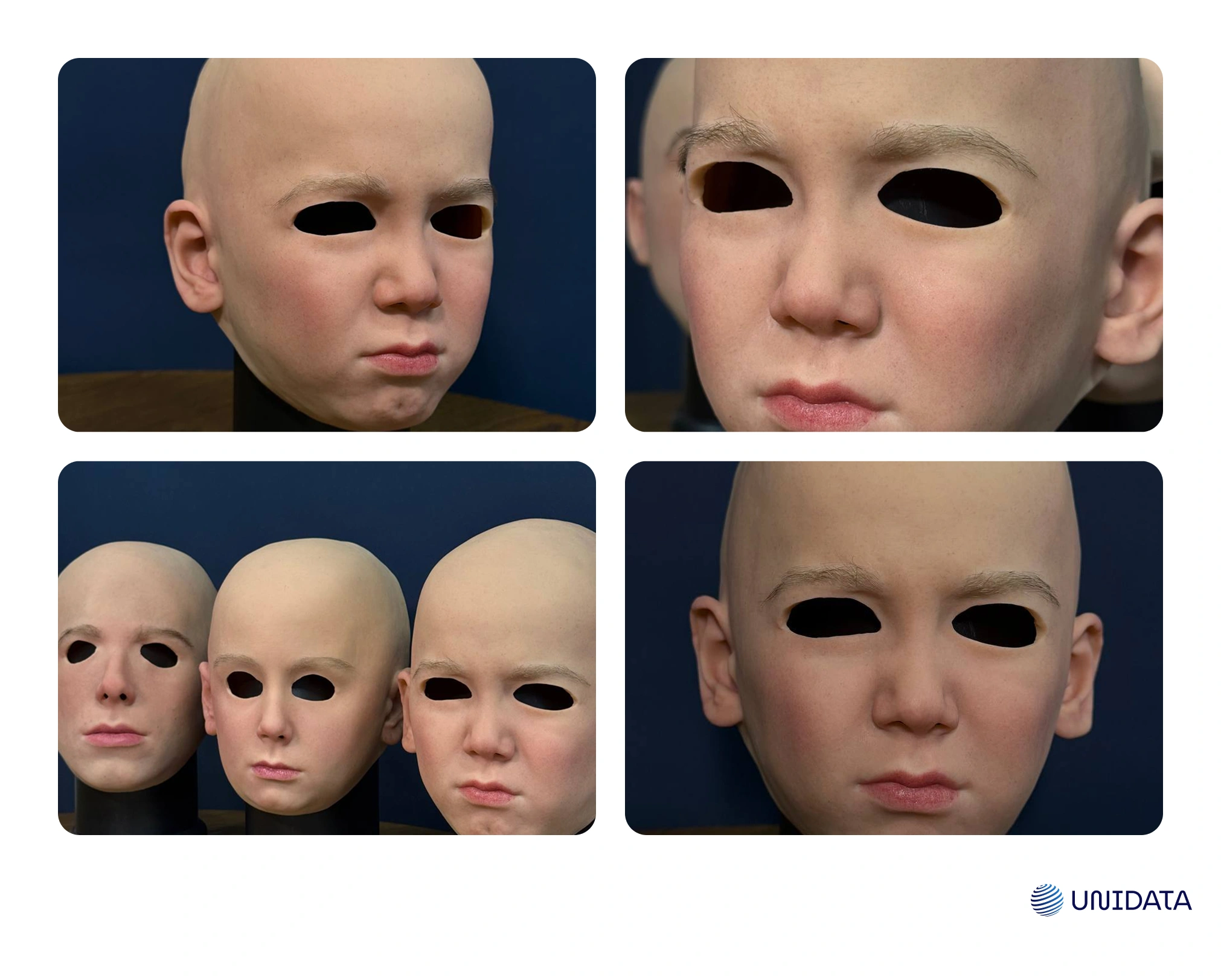

- Custom-made 3D masks crafted to imitate human skin, facial contours, and features with extremely high fidelity. These are sourced globally and often created by professional fabricators, moving beyond off-the-shelf or theatrical masks used in prior levels biometricupdate.com.

How Level 3 Hyper-Realistic Masks Are Made

Level 3 hyper-realistic masks are produced using advanced special-effects and prosthetic techniques. The process typically starts with a lifecast or a 3D scan of a real face to create an anatomically accurate base.

Artists then work with multiple grades of platinum silicone: softer blends for flexible areas like the eyes and mouth, and firmer blends for structural regions such as the nose and cheekbones. The silicone is applied layer by layer to recreate the thickness and semi-transparent look of natural skin.

The surface is finished entirely by hand. Effects artists build up realistic skin tones, pores, capillaries, freckles, and micro-textures so the mask never appears flat. Natural elements, including individual eyebrow and eyelash hairs, can be inserted to increase realism.

During the final stage, the mask is precisely adjusted for fit, breathing comfort, and visibility. Some models even include subtle internal mechanisms—thin wire armatures or pull strings—that allow controlled movement of the lips or cheeks to mimic expressions.

The result is a hyper-realistic facial duplicate that, when used skillfully, can fool the human eye and even some algorithms relying solely on visible-light cameras.

Kirill Meshyk

Head of Data Collection

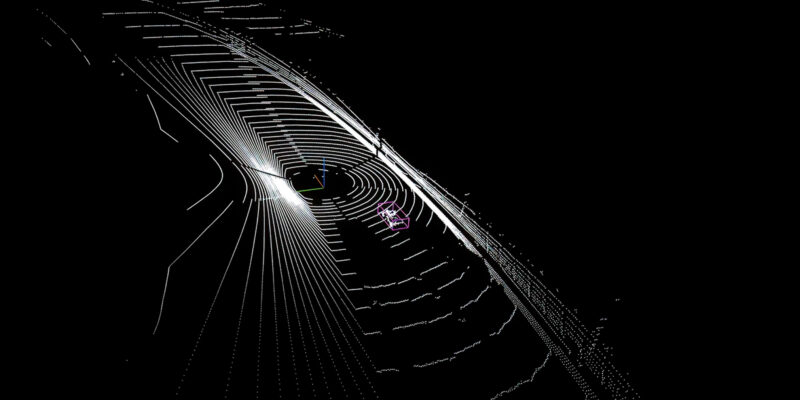

- Digital Attacks with Environmental Synchronization. The testing team may record or generate video tailored precisely to the system’s operating conditions: matching lighting, background, and motion patterns to bypass algorithms that monitor environmental inconsistencies. For example, if the properties of the target camera are known, testers can prepare video injections aligned perfectly in angle, illumination, and framing so the system perceives them as native, real-time input.

- Adaptive Attacks Against Active Liveness. If a system requires the user to perform an action — blinking, turning their head, and so on — Level 3 testers craft so-called spoof prompts that mimic the required response. This might involve a mask with mechanically controlled eyelids that “blink” on command or a deepfake animation capable of smiling or replicating head movements. As a result, even dynamic liveness checks lose their protective value: the spoof appears animated and responds convincingly to system instructions.

The guiding question at Level 3 is no longer “Can you stop a spoof?” — but “Can you survive a precision-engineered, expert-grade spoof attempt designed specifically to defeat your system?”

Each test plan is fully customized, but iBeta still adheres to ISO/IEC 30107-3 requirements. Depending on the system being evaluated:

- Subsystems are scored via APCER (attack success rate) and BPCER (user rejection rate).

- End-to-end systems are assessed with IAPMR, reflecting whether the full identity pipeline is compromised by a spoof.

Performance Benchmarks

To pass Level 3, a system must meet two simultaneous thresholds:

- ≤ 5% APCER – no more than 1 in 20 spoof attempts may succeed.

- ≤ 10% BPCER – at least 90% of real users must pass without being blocked.

This combination ensures that solutions are not only secure but usable at scale. If a system rejects too many bona fide users, iBeta halts testing until the vendor resolves the issue — a safeguard to prevent “secure but broken” deployments ibeta.com.

Comparison of Levels 1, 2, and 3

The progression from Level 1 to Level 3 reflects the rising sophistication of biometric threats — and the tightening of standards required to counter them. Each level builds on the previous one, increasing both the complexity of attacks and the rigor of evaluation. Below is a consolidated summary of the key differences across iBeta PAD levels (all aligned with ISO 30107-3 requirements):

- Attack Scenarios:

- Level 1: Basic spoofs (printed photos, images on a screen) with no special effects.

- Level 2: Intermediate spoofs (higher-quality masks, mobile video replays).

- Level 3: Advanced, precisely engineered spoofs (hyper-realistic silicone masks, deepfakes, environment-matched digital injections).

- Attacker Skills and Resources:

- Level 1: No expertise required; off-the-shelf materials up to $30.

- Level 2: Moderate skill; tools up to ~$300 (e.g., 3D printer, resin kits); partial knowledge of system defenses.

- Level 3: High expertise (testers typically have ≥10 prior PAD tests); custom tooling; budget determined case-by-case (no strict limits).

- Preparation Time and Test Duration:

- Level 1: Up to 8 hours of preparation per PAI.

- Level 2: Up to ~24 hours per PAI (2–4 days total).

- Level 3: Up to 7 days per PAI (complex custom preparation, including lighting design, motion sequencing, etc.).

- Volume of Attempts:

- Level 1: ~900 attempts (e.g., 6 PAIs × 150 attacks + ~50 bona fide).

- Level 2: ~1100 attempts (6 PAIs × 150 attacks + ~200–250 bona fide).

- Level 3: Variable/ad-hoc plan; typically >1500 attempts (custom attack cycles, iterative vulnerability probing).

- Allowed Spoof Success (APCER):

- Level 1: 0% (no successful attacks permitted).

- Level 2: ≤ 1% (virtually all spoofs must be blocked).

- Level 3: ≤ 5% (no more than 1 in 20 attacks may succeed).

- Bona Fide Error Rate (BPCER):

- Level 1: ≤ 15% (≥ 85% bona fide users must pass).

- Level 2: ≤ 15%.

- Level 3: ≤ 10% (stricter usability threshold alongside increased security).

- Environment Control:

- Level 1: Neutral, fixed lighting; no scene adjustments.

- Level 2: Limited environmental variability (partially controlled conditions).

- Level 3: Full control of environment — lighting, background, camera angles — optimized for maximum realism of attacks.

- Test Plan Structure:

- Level 1: Standardized; a single fixed scenario for all products.

- Level 2: Semi-standardized; same PAI sequence with minor vendor-specific adjustments.

- Level 3: Fully customized to the system architecture and expected threat model; designed jointly with the vendor.

As becomes clear, Level 3 is a radical departure from its predecessors. While it formally adheres to the same ISO standard, iBeta has effectively turned the evaluation into a flexible, high-stakes game of cat and mouse with the system — bringing in maximum expertise and resources. This approach makes it possible to assess a solution under conditions that closely mirror real-world attack scenarios, something the simplified Level 1/2 tests simply could not achieve.

Comparison Table: iBeta PAD Levels 1–3

| Category | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attack Scenarios | Basic spoofs: printed photos, images on a screen; no special effects. | Intermediate spoofs: higher-quality masks, mobile video replays. | Advanced, custom-built spoofs: hyper-realistic silicone masks, deepfakes, environment-matched injections. |

| Attacker Skills & Resources | No expertise; off-the-shelf materials up to $30. | Moderate skill; tools up to ~$300 (3D printer, resin kits); partial knowledge of system defenses. | High expertise (≥10 prior PAD tests typical); custom tooling; budget set individually (no hard limit). |

| Preparation Time | Up to 8 hours per PAI. | Up to ~24 hours per PAI (2–4 days total). | Up to 7 days per PAI; complex custom preparation (lighting, motion design, etc.). |

| Volume of Attempts | ~900 attempts (6 PAIs × 150 attacks + ~50 bona fide). | ~1100 attempts (6 PAIs × 150 attacks + ~200–250 bona fide). | Variable/ad-hoc; usually >1500 attempts (custom attack cycles, iterative probing). |

| APCER (Allowed Spoof Success) | 0% (no successful attacks allowed). | ≤ 1% (virtually all spoofs must be blocked). | ≤ 5% (no more than 1 in 20 attacks may succeed). |

| BPCER (Bona Fide Error Rate) | ≤ 15% (≥ 85% bona fide pass). | ≤ 15%. | ≤ 10% (stricter usability requirement). |

| Environment Control | Neutral, fixed lighting; no scene adjustments. | Partial variability allowed (partially controlled conditions). | Full control: lighting, background, angles all tuned for realistic attacks. |

| Test Plan Structure | Fully standardized; identical scenario for all products. | Semi-standardized; same PAI sequence with small vendor-specific tweaks. | Fully customized to system architecture and threat model; co-designed with the vendor. |

All test levels conform to ISO/IEC 30107-3, with Level 3 introducing custom red-team-style evaluations.

Common Misconceptions Vendors Have Before Certification

Vendors often underestimate the scale of the testing ahead and fall into several recurring misconceptions.

1. “Our system is already good enough — we’ll pass on the first try.”

Teams that smoothly passed Levels 1 and 2 sometimes approach Level 3 with misplaced confidence, assuming it’s only a matter of facing “slightly stronger attacks.” In reality, Level 3 is a completely different challenge. Systems that easily blocked photos and videos can suddenly start accepting skillfully engineered masks.

2. Underestimating the attacker.

Some engineers assume adversaries will operate naively: “They’ll make a mask — we’ve seen that, we’ll catch it.” What they often overlook is the level of creative sophistication involved: ultra-precise lighting setups, hybrid attack chains, and highly realistic movement simulations meant to probe every weakness. A model trained to reject a dozen “typical” masks may fail when confronted with an unconventional, highly creative spoof.

3. Assuming a light algorithm tweak or training on public datasets is enough.

Many believe they can fine-tune the model right before the test or depend on open-source spoofing datasets. But public datasets typically include simple, low-effort attacks and rarely capture Level 3 complexity. During certification, novel cases inevitably appear — ones the system is completely unprepared for.

4. Confusing certification with tuning.

Some vendors attempt to “fix” thresholds or adjust the algorithm mid-test (usually allowed between cycles) once early failures show up. Without thorough prior analysis, these reactive changes often backfire and raise BPCER instead of lowering it.

5. “If we’re certified, we’re protected everywhere.”

A vendor may pass the test and receive a compliance letter, but later introduce a new product version, change the architecture, or encounter new attack types. Some clients assume certification makes the system impenetrable. It doesn’t. Certification is a snapshot against a specific attack set — not a permanent guarantee. Ongoing security still requires active monitoring, updates, and continuous hardening.

In short, many vendors treat iBeta as a final milestone, when it should instead be viewed as a diagnostic step in a continuous process of strengthening biometric security.

Kirill Meshyk

Head of Data Collection

Adoption of the Standard and Market Trends

The launch of iBeta Level 3 is not just a technological step forward — it marks a turning point for the entire biometric security industry. Only a few years ago, liveness detection was viewed as an optional enhancement. Today, it is rapidly becoming a mandatory requirement for any serious biometric system. Below are the key market trends shaping this shift.

PAD as a Procurement Standard

Compliance with ISO 30107-3 has become a baseline expectation. Biometric Update describes PAD testing as “table stakes” for most face recognition solutions — the minimum requirement buyers now assume by default. Government agencies, banks, and large enterprises are increasingly unwilling to adopt systems that have not undergone independent testing. iBeta certification — particularly Levels 1 and 2 — has effectively become a trust signal in the market. In other words, PAD tests are now an industry standard: if technology has not been validated against known spoofing scenarios, customers are far more likely to question its reliability.

Rising Certification Rates and a Broader Vendor Landscape

Adoption is accelerating each year. According to iBeta and Axon Labs, by mid-2025 more than 100 biometric products worldwide had already demonstrated compliance with ISO 30107 (PAD). In 2024 alone, 46 PAD test reports were issued to 36 different vendors — well above the previous record of 35 in 2022.

Many established players are among the certified: European companies like Idemia, Thales, Veridas, Veriff, and Asian leaders such as SenseTime, Tencent, and Suprema. Notably, new entrants from outside traditional biometrics are joining the list as well. Singapore-based platforms Grab (ride-hailing) and Shopee (e-commerce) have also passed PAD evaluations. This demonstrates that the need for anti-spoofing protection extends far beyond specialized biometric vendors — major IT companies and even businesses for whom biometrics was never a core product are now prioritizing it.

Market Outlook and Growth Drivers

According to the Face Liveness Market Report 2025, the global liveness detection market will exceed $250 million by 2027. Growth is driven by several factors:

1. Stricter regulatory requirements

More countries and industries are introducing mandatory biometric identity verification — for example, updated KYC rules in financial services or national digital ID programs.

2. Rapid escalation of fraud

The availability of tools for producing deepfakes, masks, and other PAIs is pushing organizations to move beyond basic protection (Level 1) toward more advanced defenses.

3. Increasing customer demand for certified solutions

Vendors understand that having an independent validation — such as “iBeta PAD Level 2 compliant” — gives a tangible competitive advantage, enhances user trust, and strengthens the product’s investment appeal.

Regulation and high-risk sectors — especially finance and government identity systems — remain the primary drivers of growth.

Preparing Vendors for PAD Testing

Under growing pressure from tougher security requirements, biometric system developers are rethinking their development and QA workflows. According to iBeta, vendors that pass certification successfully usually take several steps well in advance.

1. Enriching training data

Teams expand their training sets — for example, by incorporating synthetic faces or artificially generated attacks — so models learn to detect even unconventional spoofing patterns.

2. Running internal trial tests

Before applying for formal evaluation, companies often conduct dry-run assessments using in-house labs or external consultants. These rehearsals replicate typical iBeta attack scenarios and help verify the system’s resilience. A small industry has even emerged around preparation kits: hyper-realistic masks, curated PAI videos, and other materials vendors purchase for tuning. While such tools can reveal obvious weaknesses early on, they do not guarantee success in the real test.

Overall, the trend is clear: vendors are investing heavily in pre-certification pipelines to improve their chances of passing the increasingly demanding evaluations.

Global Standardization and New Laboratories

While iBeta has historically dominated the U.S. market, other accredited labs have emerged worldwide, underscoring the global importance of PAD testing. In addition to iBeta, ISO 30107-3 evaluations are officially conducted by BixeLab (Australia), TÜViT (Germany), Idiap’s associated lab in Switzerland, and several others. In the UK, Level 3 has evolved under the name “Level C,” mirroring iBeta’s terminology.

This means independent anti-spoofing validation is no longer a U.S.-centric phenomenon but an international benchmark. Thanks to the unified ISO 30107 standard and the expanding network of accredited laboratories, customers can expect consistent evaluation criteria across countries — making it easier for certificates to be recognized beyond their jurisdiction of origin.

Strategic Outlook

At present, Level 3 remains optional and not universally required; many deployed solutions still stop at Level 1 or Level 2. But the landscape is changing rapidly. In finance and digital onboarding, Level 3 is already viewed as critical for confidence in system security. Analysts warn that in the age of deepfakes and high-precision attacks, passing a basic liveness test is no longer enough.

Many organizations now treat Level 2 as the new “baseline,” with Level 3 becoming a competitive differentiator. Put simply, the acceptable security bar has risen: what seemed excessive yesterday is becoming standard practice.

Likely trends over the next 1–2 years:

New modalities

iBeta is already exploring Level 3 extensions for other biometric traits — fingerprints, iris, voice. If expert-grade attacks (synthetic fingerprints, ultra-precise contact lenses, voice-synthesis PAI) become a real concern, dedicated Level 3 programs may follow.

Re-certification cycles

Today, most systems undergo testing once, typically at product launch. As attacks evolve and algorithms update, periodic re-testing (e.g., every 2–3 years) may become common practice to ensure protection has not fallen behind new threats.

Regulatory adoption

As digital identity platforms expand — such as the EU’s eIDAS 2.0 initiative — certified PAD may become a legal requirement across more jurisdictions. Policymakers increasingly recognize the risks of biometric fraud and are likely to formalize independent anti-spoofing verification in legislation.

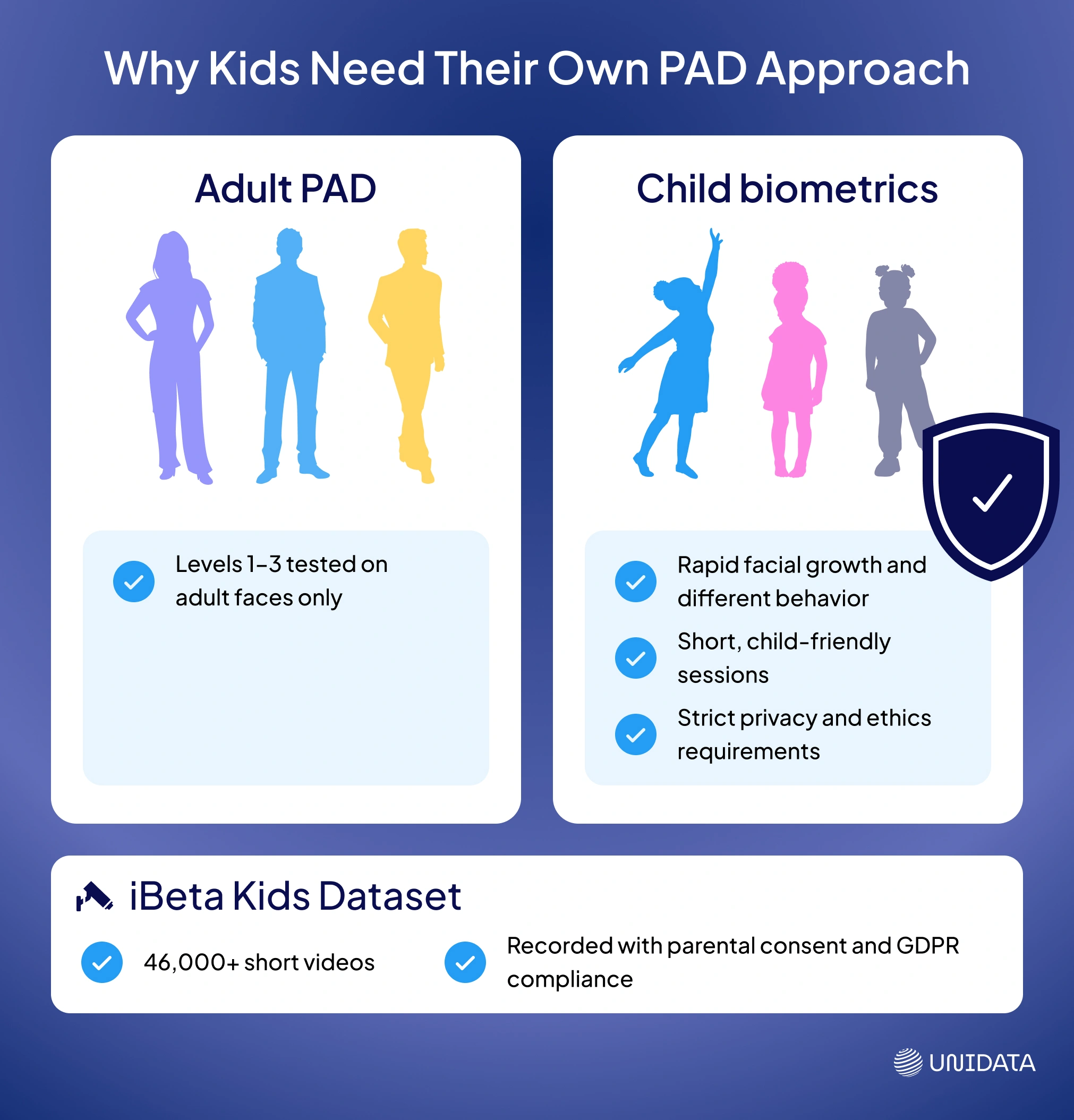

Biometrics for Children: New Challenges and iBeta Kids

One of the most promising — and most complex — areas in biometric security is ensuring reliable liveness detection for children. At present, iBeta PAD Levels 1–3 are tested only on adults, but the industry is increasingly recognizing that children are not simply “small adults.” Their biometric patterns behave differently and require a dedicated methodology. There is no formal certification program for child-oriented systems (“iBeta Kids”) yet, but the first steps in that direction have already been taken.

A key milestone is the creation of the iBeta Kids Dataset — a collection of more than 46,000 short videos featuring children of different ages, recorded under varied lighting conditions and subjected to common spoofing attempts (2D photos, 3D masks, video replay). This dataset is designed to train and evaluate liveness algorithms tailored to younger users.

The project was carried out by the Unidata team with strict adherence to ethical standards. All data was collected with informed parental consent and is fully compliant with GDPR requirements for personal data protection.

Why Kids Are Biometrically Different

Facial Growth & Variation

Children’s faces change rapidly, often lacking the distinct structure adult models rely on. Systems trained on adult data may misread a child’s shape, texture, or proportions — leading to higher false rejects or missed spoofs.

Behavioral Gaps

In active checks, kids don’t always blink, smile, or turn on command. Some stare wide-eyed; others fidget. A system expecting adult micro-expressions may flag a genuine child — or miss a spoof like a sibling photo.

How the Child PAI Dataset Preparation Differed from Adult Data Collection

Working with child-focused presentation attacks required the team at Unidata to rethink and adapt many parts of the process.

Physical parameters and face geometry.

Children’s faces are smaller, with different proportions and spacing between features. Standard mannequin heads and adult mask forms don’t scale well, so in many cases we created dedicated child-sized masks or custom 3D molds to ensure realistic spoof material.

Shorter, child-adapted recording sessions.

Children have limited attention spans and tire quickly, meaning spoof-recording sessions — such as capturing real child footage for replay attacks — had to be shorter and include breaks. Unlike adults, a child won’t repeat attempts for an hour. The workflow must be fast, engaging, and playful to prevent boredom or frustration.

Equipment adjustments for child anthropometry.

Tripod height, camera angle, and lighting all required recalibration for smaller participants. The lab setup was frequently reconfigured to match children’s height, posture, and natural movement.

Behavioral considerations during spoof recording.

Capturing replay-attack footage often required the tester to use a child-psychology-aware approach. Parents and animators were invited into the lab to create a relaxed, comfortable environment. Without this, natural behavior — essential for realistic PAI samples — becomes difficult to record.

Safety and ethics.

Working with children required expanded safeguards: a responsible adult present at all times, strict session limits, and strict controls on how footage is stored. Videos are anonymized with unique IDs, and access is restricted to a small authorized team. Written parental consent was required, with clear communication of the project’s purpose and significance.

Through these adjustments, the lab established a dedicated workflow in which equipment, staff, and scheduling are tailored to young participants, ensuring high-quality data without causing discomfort or risk.

Kirill Meshyk

Head of Data Collection

Why This Matters Now

Safe biometric identification for children is becoming increasingly important. Real-world examples include remote learning systems that require verifying a student’s presence, school access or meal-management systems, and online platforms that enforce parental controls. Child-focused PAD is already starting to appear in commercial products — some companies are even using the iBeta Kids Dataset to adapt their recognition models to children’s faces.

However, there is still no dedicated ISO standard or official iBeta certification track for child data. In the future, we may see programs similar to “Kid-safe PAD,” requiring vendors to demonstrate that their algorithms work reliably on child-specific datasets. Until then, customers looking to deploy biometrics for children should ask vendors a direct question: has the system been tested on a child dataset? Experience shows that models trained only on adults often fail when used by younger users.

Any expansion into child-focused biometrics must prioritize privacy and ethics above all else. There can be no compromises: data collection must be transparent, storage must be secure, and usage must be strictly limited to keeping children safe. If iBeta eventually formalizes this area, it will need to design dedicated ethical protocols — including rules for creating, storing, and disposing of child-related spoof artifacts.

Solving this correctly will improve fairness and robustness across biometric systems. Just as earlier PAD benchmarks helped expose gender and racial biases in algorithms, a child component would reveal age-related discrepancies and motivate vendors to fix them. Ultimately, everyone benefits — especially the youngest users, but also society as a whole.

Conclusion

iBeta Level 3 redefines what “secure” means in biometrics. It simulates expert-level attacks, enforces stricter metrics, and sets a new bar for trust. For vendors, it's a credibility signal. For buyers, it’s a new baseline.

As threats grow smarter, Level 3 is fast becoming the standard for systems that can’t afford to fail. If your solution isn’t tested to that level, the market — and your users — will soon ask why.